At this point in the space opera, the more sophisticated reader may now find herself wondering: What on Earth II-kinda reason did these middle-aged, middle-class mortals have to suddenly dare be so angry—much less the time-privileged, if impecunious, Elysian Fields Gods?

Well, as for the business-drone Gods, it was surprisingly simple: Living forever might sound great—until you take out a thousand-year mortgage with compound interest.

The mortals, though? Yeah, they had so far been able to force themselves to feel content with their humble but sometimes comfortable lot.

But that force was lent them by a fatalism that had now had its philosophical pillar kicked away, like a unicycle from under a clown.

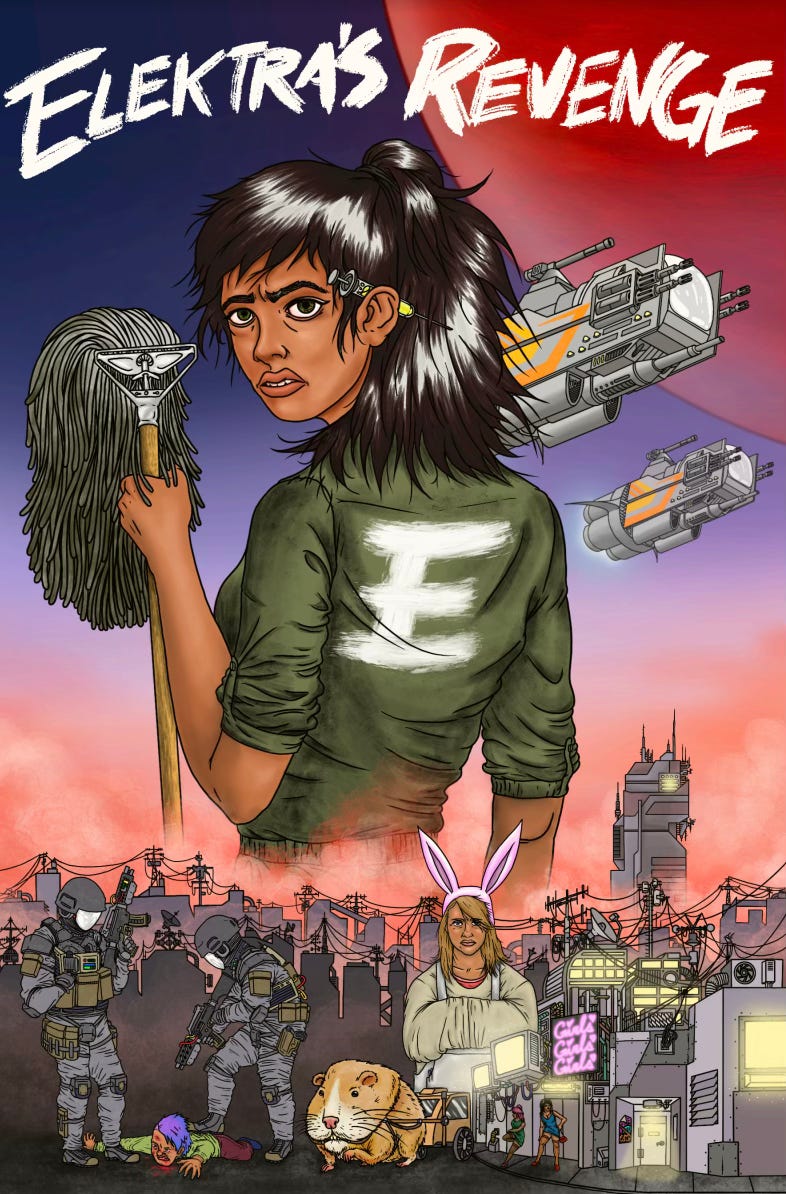

The obvious, inborn difference between the mortals and their betters had been the cornerstone of the social order; it was the reason your Elektra-types had to accept being told they weren’t good enough for theater.

As a young mortal, as your first auditions unfolded, your eyes and ears might report that you had the talent—that it was only the unfair, unwritten rules that held you back; that the God who got the part hammed relentlessly, and even the judges’ sad eyes loved you, despite themselves. Sure, we’re all biased towards ourselves, but you watched other mortals who should have won a part, too, and watched them lose out, same as you.

You felt so sure you were getting better, getting too good to ignore—that maybe you would be the first to go over the top!—but after dozens and hundreds and thousands of back-to-back rejections, the evidence of your own eyes and ears no longer seemed so clear. Maybe what you thought was hamming was power. Maybe your subtle skill was mousy and lame. You slowly accepted the explanation that Gods always got the parts because Gods always happened to be better. If you were really that much worse than the scenery-chewers who always beat you out, maybe you didn’t deserve to be onstage.

These worm-food artists had been bowed and broken till they were grateful to be the lily pads, while a deathless Ophelia lay in the river, pretending to comprehend sadness and forgetting most of her lines.

Vaguely, they remembered how well audiences had reacted to them back in school. They could still remember the spellbound looks on their faces. And now they could hear that Ophelia was stammering; they could see the bored mugs in the audience, attending only because there was no other form of entertainment they could choose. But if the Gods were superior, well, OK, then... OK… the artists’ outrage was dampened by years of surviving shit-jobs, daily life, and mounting addictions, illness, madness.

But now you tell us there’s no difference between gods and mortals?!—except for the fact that mortals were stronger from a hundred generations of natural selection in the mines!—then all their failures, borne in shame, had been lies—

—murderous lies.

Lies shouted at them while they were muzzled. A childhood of working like an adult at theater studies, then a lifetime of being told you weren’t good enough... ending up in a laundry… giving up, waiting for the end… and now they tell me it was lies?!

Not only were their lives shortened by the Gods, they were ruined! Smugly. It was a kind of murder—the word that now rang in all the streets.

The unrest that Cook and Diana had seen as they crossed the city, though often silly, was almost personified frustration, a mass mourning for murdered dreams. For creative force stuffed and throttled. Even the untalented felt cheated—which might be the greatest tragedy of the entire situation, Diana joked to herself.

Then she admitted: sure, maybe Mop Bitch was talented enough to make hers the biggest tragedy. Why the heck not? She was good enough at acting that most of the customers had never noticed she was bat-shit insane. Diana chuckled to herself some more.

Diana had never spent much time in New Tiber—she figured it was solid psychos, big drug pushers, and turbo-pimps with surgically implanted brass knuckles. She wasn’t completely wrong—though the South Corridor as they approached the bridge was more business-friendly, running a few reputable sweatshops and distribution warehouses. At the wagons and taverns that fed most of the area, it was now the shift change. But nobody was picking up the shift. Instead, the joints began trickling their grease-stained drudges into the streets.

Many of the employees, once theatre hopefuls, hadn’t hoped for anything in decades. But now the Elektra Burgundy rescue squad clamored past the dive bars by the New Tiber bridge—passing right at the moment when another coiffed reporter on the bar TVs was bragging about how well the trial was going and how peaceful the city had remained.

People laughed: they heard the reporter’s syrupy voice as they watched the motley whores and students clank by, well-armed, feeding the disturbance. Most heads had turned away from the televisions, looked out the storefront windows, and then turned back to their fellow drinkers. They ignored the TV screens and even their beers in favor of asking each other what the f@ck was really going on. If so much as one person knew, then suddenly the bar was empty and the street was full.

Diana looked back, watched a hundred fists waving through smeary barfront glass, and smiled. The rescuers could now hear shouting in the city behind them, shouting that coalesced into chanting—even a couple of explosions.

All good things, tactically, even if the self-righteousness of group chanting normally made Diana sick to her stomach—granted, in her experience chanting typically came from, say, slightly violent clients protesting the injustice of their pre-ejaculate ejection.

At this point, being quiet wasn’t working all that well. When the GOs whom Cook had moments ago knocked flat on the approach to the bridge woke up, they would radio in to their nests. And it would be nice if the GO forces already had multiple shit-shows on their hands.

As they passed the pile of bodies, the kids ferreted the GOs’ pockets for packets of Lyfe. Cook snorted over his shoulder at them, pointing his big pot impatiently toward their fate in Syd. Diana was beginning to suspect he was high on something or other, but it certainly wasn’t Lyfe.

Now they crested the bridge itself, marching into the dark as the city lights began to recede behind them. Suddenly, the whippersnappers went silent at the sight of the stars, the beautiful balls of gas which most of them had studied in school but none had never seen, growing up in Heaven’s all-night haze of light pollution. “Like candles in the air!” a young girl breathed.

As the orbs grew bright and majestic in their velvet case of black, the young people quieted. They knew from textbooks how many miles across an average star’s bulk stretched, and how inconceivably distant they were. Most of them had, insofar as they thought about it, vaguely imagined the stars would appear as circles in a properly darkened sky—like the bright disk of Earth II. They had come from one of those stars. It couldn’t be that far.

But from the neighborhood of Sol II, even in the dark of a Syd night, all the other stars looked like single points in space. Like someone had coated a lightbulb in black stage paint and pricked it with the tiniest pin.

How could those be suns? They’re so small they don’t mean anything.

How did we ever get here from there?

Were we giants?

For the first time, many of them realized that their lives, and even their way of seeing the Universe, had been incredibly small and strange. Strange, because anything in a distorted scale becomes incredibly strange. Unless you were one of those poor slave miners down on Earth II, your entire hamster cage was the size of New Jersey. Sleep deprived, Diana looked up and had a brief waking delusion that they had all gotten locked on the wrong side of some wormhole or time warp. The real human race was on the other side, wondering where they’d gone and hoping they were OK.

Cook looked up himself, looked back at the kids, and smiled wide for the first time in years. “Lonely place,” he said.

Then he marched grimly on, picking up the pace.

They filed after him like a row of chastened ducklings. The only sound besides the clump of feet was the sniffling of Rhoda and Purdue, who had begun to cry again. Diana clocked each girl lightly with her purse.

Meanwhile, off camera, Elektra was in a shower cell outside of the court.

The cell was lined with grey-blue ceramic tile except for the drain in the center. The air was damp and putrid with the bodily humors of whomever they’d hosed down there last. She was power-washed, then wiped with disinfectant by mildly disgusted GOs; she had lost control of her bodily functions again, but she smelled nowhere near as bad as a dead Anihil.

All she noticed at the moment, in her tunnel-like prison of withdrawal from Thyme, was the porous ceramic tile, that horrible depressing grey-blue tile, an institutional mockery of the sky she would never see again. She tried to say something about it but managed only a gurgling cackle.

They carried her to an even more depressing room with pure white walls. At least it was dry. They put her into a fresh nylon pantsuit, applied an antique catheter and colostomy bag, and attached her, wrist and ankle, to a sturdy cot. Which was good, because she was beginning to thrash involuntarily. They inserted a leather bit to keep her mouth unbloodied, and gave her another shot of Lyfe because they had the night shift, and it would be boring otherwise.

Around 3 AM the cot broke and they had to get a fresh one.

The next morning, Elektra was propped up in a red velour chair in the middle of a three-foot-square scrap of pink satin moonsilk. She sported her little suit from the day before, cleaned and pressed.

Behind her was another three-foot square piece of pink satin, hung vertically to make a backdrop. Beside her was the same reporter-woman, in a fresh pantsuit of her own. A camera completed the makeshift studio; what was on-shot looked like a low-budget 1960s version of the inside of a genie’s bottle. Off camera, the grey concrete of a high-walled interrogation chamber stretched and echoed around that patch of color and light.

The reporter waggled a microphone under Elektra’s chin, grunting under her breath in frustration. “OK. No comment, I take it? Let me phrase that question a different way.”

Elektra tilted her head and volleyed back with a slightly different blank stare from the one she’d been employing for the past five minutes. A shining drop of drool fell on the microphone with a soft thwap. She smiled.

The reporter tried to smile back. “I’m just trying to understand... You come from an extremely privileged family, don’t you? The notoriety of Lemon Burgundy, all handed down to you! And the Equal Arts Act was passed just in time for your generation. You could have been the first mortal theater star, couldn’t you have?”

Elektra tilted her head back the other way and made a soft snurking sound.

“The stage was practically set for you! I would have done so much more, personally. Such nice olive skin… maybe a bit pale...”

Elektra was pale indeed, today, although the pallor was remarkably green; she gagged back some vomit and turned slightly greener.

“...talented—talented for your sort, anyway—beautiful; you had everything growing up that a young mortal could possibly dream of. You had everything most people can’t even hope for. So lucky, and you went so wrong. How can you justify—”

“Hahahahahah,” Elektra said woodenly. “Dream.”

“Can’t you give me any idea how such a lucky young person went so terribly wrong?”

“Hahahaha. Lucky! Yes.”

“Yes?”

“Yes.”

The reporter stood up and mic-dropped. “Look, Oribe, this can’t even be edited. I’m going to strangle this jagbag. Are they sure I can’t get her any drugs now?”

“They know what they’re doing, Sybil. She’s on a schedule. Do your own job.”

“What is my damn job? I was supposed to be on theater openings this week. My degree doesn’t say dipshit-sitter on it.”

“Dipshits!” laughed Elektra. “Half-wits!”

“Shut up, worm food!” Sybil testily stuck a monogrammed syringe into her own arm. “Goddammit, I knew I should have gone into dancing. My father had to have his—”

“Father,” Elektra said. Her glassy eyes went moist, flickering over the bleak cell and the little satin spotlight. “Daddy...” She began to sniffle, and her eyes cleared up a bit. She looked up at Sybil and chewed on her lip, beginning to remember why she felt angry. Out of shot, her hands were tied to the chair.