Technically, Joe’s Dogs wasn’t a hot-dog stand: it was a hot-dog restaurant. But not for reasons of dignity.

Joe, the owner, had modelled it after wiener stands in his native Chicago, but the distance north from Chicago to Madison made the weather one tick too bitter for serving outdoors. Down by the university they had some food trucks in the summer to give the remedial students that ol’ boho, I’ve-been-to-Tijuana feel—but they were serious van-trucks, with the kind of Rube Goldberg heating setups that are probably illegal now. Joe wasn't the kind of guy who would make his employees sell pork anus out of a nuclear reactor.

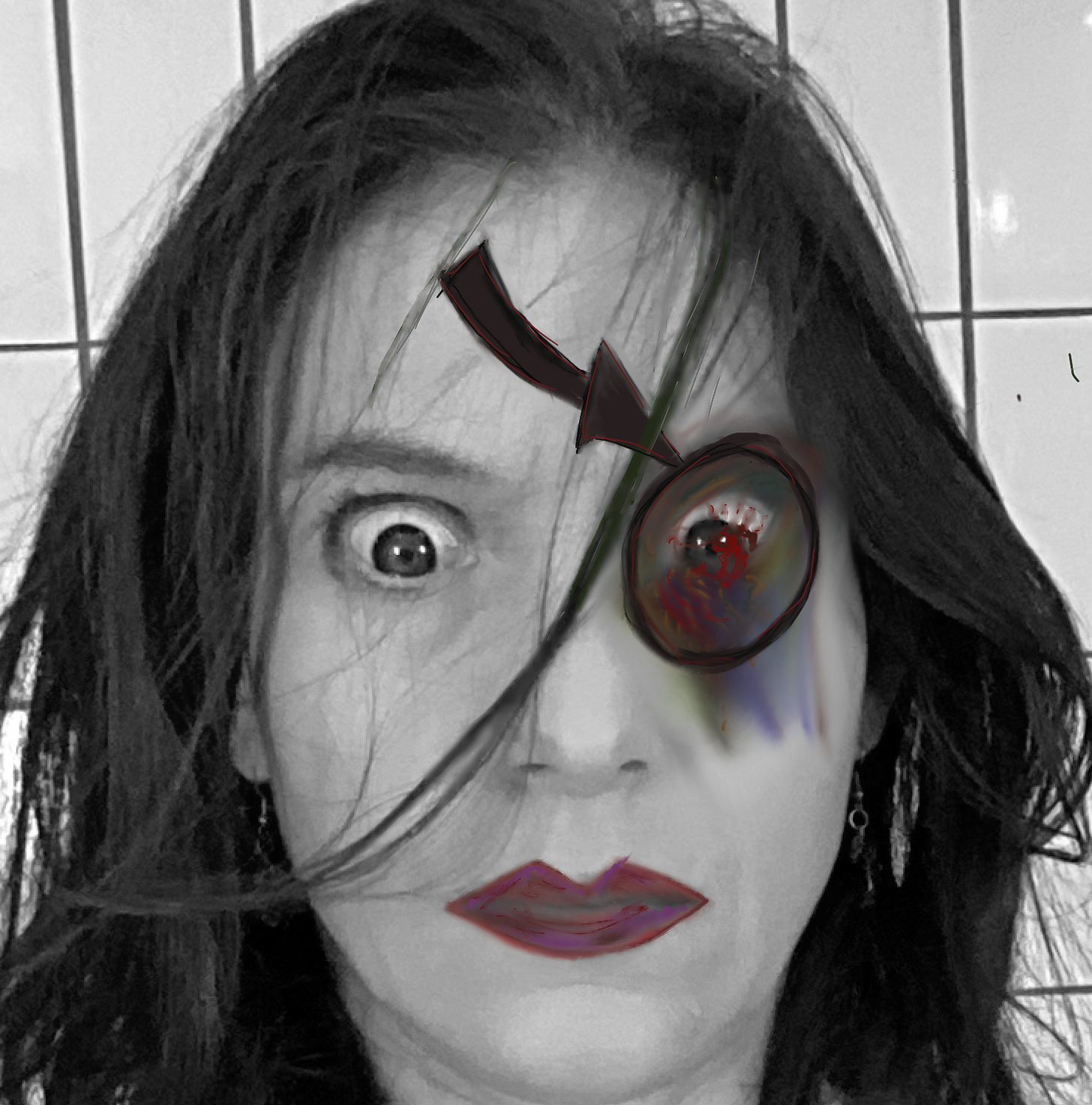

I hoped Joe was also not the kind of guy who sh§t-canned his porcelain sanitation engineer for coming in looking like she got pimp-slapped.

Now, in the summer, it was a beautiful walk down there, despite my mushy eye and fading hangover. Floating in my giant, red hot-dog T-shirt and Army shorts left over from Vietnam, I was comfortably invisible, at least with my hot-dog-themed baseball cap pulled low over my villanous visage. I was born a grumpy little old man, with young feet sockless and sensual in sneakers, and Death already nagged me to savor those scant summer days.

I didn’t know it—I didn’t know the other latitudes yet—but up there near the top of the planet, even the light of July wasn’t really summer, still pale like an ice-cold lemon.

But, for the moment, I was earning a princely seven US dollars per hour, at least at the Claude-brewpub job, and I was new to Joe’s and full of optimism about it, so did I give a sh£t? It wasn’t my dream, except it wasn’t NOT my dream: When I was a kid, I actually planned to be a waitress.

No; seriously. It started with a Catholic Youth Organization brunch. People were cold when my hands were empty. But when I came scurrying towards them with their coffee and doughnut faster than they thought it might arrive? Nothing but smiles!

Bless my little heart, I thought it was fun making people happy.

It’s also impossible.

Sure, I really wanted to be an astronaut, but that’s not the kind of thing you could do. People from, like… somewhere else got to do that. Suburbs, movies. Who knew how? I thought they only showed kids wanting to be an astronaut because it was so silly.

“I want to be a foreman at the mill!” “I want to be a garbage collector!” What do you want, Lucy? “The universe!” (Class bonds through gales of derisive, prematurely-embittered laughter.)

My best-realistic-case-scenario, fancy-dream job was doing music or writing books—maybe the outcome was doomed, but you could start without an entire spaceship.

For books, you didn’t even need a word processor yet, although businesses were starting to switch to computers. Which seemed great at the time, because I got all their discarded typewriters from the trash for free.

Once you typed a book though, nobody seemed to know what to do with it; waiting on your luck seemed to be the only option. But I could wait, because I could wait tables! My aunt did it, and it seemed all right. If your dreams didn't work out, you would always have a way to make a living.

Then I got my first waitressing job, and found out that I sucked.

Really, dismally, I slurped.

I had never in my short life run into anything I couldn’t learn to do, and then...

I never knew why, but as badly as I wanted to make the customers happy, that’s how much they hated me. Pretty soon the feeling was mutual. You’re so ugly when you’re hungry. All of you. Slow your roll.

So much for Plan B. But they always needed a porcelain sanitation engineer.

At the time, I thought the reason I always wound up hidden in the kitchen was the way I looked, but…

JESUS! We’re NEVER going to get back to talking about poor Brett, are we?

It's not me alone. This was half the guy's problem. Brett Wentzel brought out the narcissistic sadist in everyone—if you noticed him. His desire to be noticed and his desire to be left alone were equal, and both so intense, he tended to register as a burned-out hole in the fabric of reality.

A black hole, chowing down on a star.

I grabbed some blackberries from a hanging branch and stuffed them in my mouth, subconsciously hoping they were slightly fermented. Instead I got a mouthful of the lead dust that floated up from the drive that went under the new convention center.

Heh, heh… “Convention center…” Sorry to take a detour the moment I almost clearly remember Brett-our-hero again, but I can’t help myself giggling:

The phrase “convention center” was such a trigger in that time and place that I still get a kick out of mentioning it. God d%mn, it turned out ugly. The local hippies and ecologists had tried to block the center’s every construction for years, because there was a risk to a rare fish or frog or, more likely, one of their leaders’ lakefront view.

As usual with this kind of civic tempest, both sides lost, after a battle of inches. There it was at last: the magnificent Madison Convention Center, conceived to breathe economic life into the town outside the university, and it finally got to live… but as an ugly, hamstrung, colossal failure whose surly managers chased off most of the businesses that were supposed to fill acres of wasted orange carpet.

Between the delays and budget cuts and maybe the creation of a tiny detour trail for frogs—that last was my imagination, but it would have been cute—by the time it was usable, all the conventions it was supposed to attract had picked less mulish cities.

But it did a great job of backing up traffic. And of being a hideous landmark—it meant I was almost downtown. Joe’s Dogs, here I come!

Poor Joe. He had a five-year lease on a building that had seemed like a bargain, right behind the state legislature's boob-like rotunda, looking down on the accursed convention center and Lake Menona. But it was on the opposite side of the capitol square from State Street, whence Joe’s high-quality but affordable flesh tubes would have drawn a student clientele.

It was nestled instead amongst the parking garages, so most of its foot traffic was junior legislative staff on their way to their cars, driving straight from a labor violation to bed. The drunks looking for french-fried not-fingers came within blocks of us, but never quite near enough to see our gloriously phallic neon sign.

Joe was so proud of that wiener sign.

The only real advantage of the location turned out to be a great view of the capitol building, which drew a few tourists by word of mouth.

But the squat garage that cut off our view of most of the cross-halls left the rotunda sticking up as a smothering Freudian metaphor for Joe's life, and the lives of his employees—how we had gotten dizzy and disoriented at a fork in the road which none of us had noticed, much less understood.

Or that’s what Joe said after Joanna’s cousin—Joanna was our self-appointed shift manager of sorts; she was such a control freak she did extra work for free so she could hold it over everyone’s head, including Joe—came in to beg for stale food and slipped him that Molly.

Jesus, I forgot about that! Joanna’s family was always sneaking into Joe’s through the alley door, begging her for money, stealing food, and wreaking havoc. We got to know they were coming by the smell.

If that’s what her whole lot in life was like, in retrospect, maybe we shouldn’t have been so hard on ol’French-fingers (you’ll find out; it’s nothing sexual, brrr). But we didn’t think twice, since nobody cut us any slack; it was a hard time and a hard place and she was a pain in the ass on a daily basis.

So when Joanna absent-mindedly dipped her fingers in the deep fryer while she was bitching out Kerry Ten-kids for having less-than-magistral eye-hand coordination—we laughed.

It would have been nice if some adult at any point had tossed us a clue. But we had the feeling we were being launched upon dark waters unlike any our elders had ever known. Who knew how much of the adults’ cluelessness was genuine, and how much of it was defensive?

My own father had two pieces of wisdom to pass on: “Life's not fair,” and “If you have to be a dishwasher, be the best dishwasher you can be”—the latter being, as you may recall, terrible advice.

But at least it was a sincere attempt to be helpful, probably. People his age in Wisconsin didn’t seem to come from the same world as the “baby boomers” you saw talked about on TV.

As I moved further through the world, in the better places, the more powerful middle-aged were so fascinated by their own youth and glamour—and so determined to hang on to it—that they snuffed out others’ youth entirely. But there are some kinds of people in Wisconsin who haven’t changed all that much since color television, and they might be the same at the end of the world.

Or maybe the capitol rotunda looks less metaphorical if you don't have a hangover. Or Molly. At least I wasn't late.

Though I still had reason to scuttle when I arrived. Prescription sunglasses were still something of a luxury, so people were used to seeing me with a mess of plastic on my face: my regular glasses, with dollar-store sunglasses perched atop them further down my nose. I am serious about looking.

But when I walked through the dark building to the basement—punched in and tied on the plastic apron, then turned and stumbled over a box of T-shirts Joe had dumped in front of his office door, all still wearing my dark glasses over the regular ones—Joe’s shit-seeking antennae popped up from his skull like deely bobbers.

Unlike myself, Joe was born for the restaurant industry: There was nothing that amused him more than a disaster.

Hm... when I put it that way, who's to say I wasn't made for the industry myself?

….Whoever decided to make me the kind of person who tripped over anything unexpected that was ever placed in my way—that’s who it was that would have said it, I suppose.

It didn't matter: If you were young, unconnected, and too goofy to serve state senators or work at the call centers where most of the goth kids avidly served the Prince of Hell—otherwise known as capitalism; they were such well-dressed hypocrites—then a clown collar was your destiny.

If you wanted to be fancy and escape Madison’s gravity sink, the kind of two-dollar raise I had received at the brewpub was maybe insufficient, but it was necessary.

I could almost smell my escape.

Joe showed no desire to get out. He started in the same city everyone else was trying to get to; New York was for astronauts— but also, we natives were a prime font of slapstick. Why would he leave?

I heard Joe sneaking towards me now, but too late; I tried to shy away with my delicatessen face, but too slow:

"HA!" He snatched away the sunglasses. “Oooooh,” he said. "Awwwwwesome," he continued, reverently drawing down the regular glasses to gently palpate my mush. "Hehehe."

"Ow!" I said.

"Ahh, that doesn't really hurt."

I sulked.

"Don't cry, let me get you something for it."

"I wasn't crying!”

I had exactly enough time to fantasize about a Vicodin, like Brett Favre got to eat—chloroform, even?—before Joe came bustling back with a Sharpie marker.

"What the—"

"Shhhh, shh shh. Daddy Joe is gonna make it all better." I rolled my eyes but held still while he drew a giant, black, indelible-ink circle around my shiner. Then, he clamped his tongue in his teeth, nodded to me with a grin, and started to scribble.

I finally had to break character and laugh: "Did you just draw a giant ARROW pointing to the CIRCLE you drew around my black eye?"

"Yep! I told you. Listen when I speak, child.” He was, what? Twenty-seven? “I'm gonna make this shift better for us all." He cocked my stupid hot-dog ballcap to best highlight his handiwork, then gently replaced my slightly-bent glasses.

"Mona Lisa, part two." He put his hands on his hips and nodded. "One adjustment, though: Take off that plastic apron. Tonight, I'm promoting you to the cash register!"

"What?! Oh my god. Oooh, holy shit," I said. "Aren't you afraid I'll scare the—"

"You're finally scary ENOUGH for my customers," he said proudly.

"Does this mean I get a—"

"Weeeeeeeeeee’llllll see if you deserve a raise, OK, Rocky? Cause there's a difference between keeping the customers in line and costing me money. So you'd better be smart. Can you be smart?"

"Like, smarter than I am already?"

“God help me.”

I made a straining noise and a toilet face. "Uggggh, it's more likely I'm gonna be able to grow a tail."

"You do that, I'll make you regional manager."

"R— you only have one restaurant!"

"It takes a while to grow a tail, kid." He grabbed me by the shoulders and turned me toward the stairs. "Now, get up there and don't be a dumbass."

"Aren't you going to show me how to use the cash register?"

"BE SMART."

"You don't know how to use it, do you?"

He pretended to look sheepish. "It's one of those new POS things, in my defense. Point of sale, piece of sh@t. I paid for the motherf£cker, so it's your job to program it. You got me."

"In other words, go ask Joanna?"

He stuck out his hips and did a Joanna impression. "Yuh, I sphtoth you could asthk Joanna."

Joanna French-fingers didn't lisp, but that was Joe's impression of nearly everyone he didn't like. Which was probably all of us. But especially Joanna; I think he probably needed her—she did an incredible amount of unpaid and unasked work sheerly out of her need to tell other people what to do—but they hated each other with an intensity that provided daily amusement for us all. “Now get the fuck up there and keep the rabble in line.”

Up top, Joanna barely looked twice at my eye. She was more unimpressed by the fact that I believed Joe. "Of course he knows how to run the new register! He was up all night reading the instruction manual when it came in. When is anyone but me going to learn that guy never means a word he says? He's trying to see if you think he's stupid, so he can catch you trying to get away with shit. Well, he’s clearly also shoving the job of training the mouth-breathers on to me. Am I the only person in the world who doesn't fall for his shtick?!?! I swear to god, if any of you had the brains to wipe your as£s, maybe I wouldn’t be giving myself cancer with all this godd@mn r&tard-induced STRESS. If you had even the slightest consideration—”

“Stress? Do you have to use buzzwords? You sound like my moth—”

She was a thousand miles away. “… god-d£mn stupid-a&s pack of ##&£ di&£ ££&ing dumb *&# %ing mouth-breathing #£&#—”

“OK, OK,” I said. “I’m standing right here.”

Joanna was one of those "I'm the only one who gets it" people, as you might have divined.

She didn't have kids yet, because she couldn't find a guy who could tolerate being treated like one. But as any lady with a baby who was foolish enough to set foot in Joe's Dogs could tell you, her biological clock was ticking so loud even in her 20s that her teeth rattled. Joanna was born to relish abusing authority, any way she could get it, and she had a habit of referring to every hot guy who walked into the hot-dog store as “the future father of my sons.”

"So how DO you use the register?" I said, suddenly tired.

"Wait... so… in case I’m hallucinating from sheer fatigue—are you seriously trying to tell me that Joe wants YOU to learn the REGISTER?"

“Yup!”

"With—that—face!?” she snapped. She hadn’t really noticed my black eye yet—she meant she hated my regular face. But I pretended not to understand:

“I’m pretty sure it made his day.”

Dull look: “You two aren’t pranking me?”

“Not as far as I know, Captain.”

She worked her lips and fingered her “My second language is sarcasm” keychain—no doubt purchased from the bumper-sticker store at the Dane County Mall—in neurotic rage. “What’s next—he’s going to hire an actual monkey?”

“TECH-nically, we’re ALL great APES.” I stuck my face in her face and gave her a grin.

She finally looked past my glasses, figured out what I meant by “it made his day,” widened her eyes involuntarily, then shook her head, her slack and chubby cheeks swaying on the breeze.

"Of COURSE… he would DO this TO ME… JoooOOOOOOE!" She howled and shook her fist dramatically in the direction of downstairs, pink with rage. "I feel like I'm married to the motherfucker."

From the basement came a faint theatrical retching.

"Sounds like he would be too honored to get into your chino shorts, there," I chuckled. "Don't worry, it's not awkward."

She goggled at me hatefully through her huge, round eyes, those blowfish cheeks converging on what could have been an alluring rosebud pout. I never knew whether to feel bad for her over the way she looked, or whether she, at 25, had already received the face she deserved.

None of us were supermodels. Else we'd have been working at the Palmer House. But when it came to mixing martyred fantasy up with reality and then letting the resulting slime fall out of her mouth at the slightest provocation, old French-fingers was—I have to hand it to her—ahead of her time.

“Anyway, Sunshine-tits,” I continued, “your incomparable perspicacity in the endeavour of dissecting the foul, suppurating innards of the human animal is not going to change the power of Joe's appalling laziness, ever, so why don't we start in on that fancy computer?”

The mouth flopped further open, and I put a finger to her lips.

“Mmmm. I know that if I’m running the register, that means you run the risk of incurring physical labor for once in your life, but I know you’re younger than you look or act. You’re sure to survive.”

French-fingers’ lips pulsed for a few more seconds, digging for a 50-cent word. Being the most intelligent person in history, Joanna got visibly incensed when you confused her.

“I’m gonna spend the entire shift resetting the machine after you mess it up,” she said finally. “But if you’re soooo lazy that you need me to do everything except the register, then here...”

She pottered over to her “territory.” Christ. She had turned part of the back kitchen counter into a weird, personal desk-like station, with a mass-monogrammed Wisconsin Dells pen jar that said “Jo,” annoying boxes of tea, a pallet covered in snacks from home and sentimental 1980s office-style junk, and a metal slotted desk organizer—all gathering greasy dust. It was probably against the food purity laws. But as many times as Joe dismantled it, she would pull it all out of the Dumpster and start over like Lazarus the next day, so he finally gave in. So long as she didn’t manage to arrogate to herself an office, title, or raise.

She scrabbled around officiously in there and pulled out a booklet. “You can teach yourself to run it. I have HAD it. Here’s the manual. I’ll be mindlessly doing the potatoes, pretending I’m you.”

“In that case, you’d better schedule in time to—”

I glanced at the front door, which had already been open for three minutes, and timed my last word to coincide with the grand entrance of the dinner shift’s first table of customers:

“—maaaaaaasturbate!”

It was a lady still wearing Reeboks and a flowered dress from the 80s: Frosted blonde helmet-hair, tiny gold cross, noodle worms of mascara, with two prissy daughters and a sperm donor in tow—the kind of Madisonians whose fondest dream was to move to Naperville, Illinois and become villains in a John Hughes movie.

They’re probably in hospice now, the daughters spent and sad.

They blinked, unable to process the audio input. Joanna looked daggers at me; I cocked my hips and sang out, waving like Kermit the Frog:

“Welcome, Earth Creatures! Who wants a HOT DOG?!”

“I hate it here,” Joanna muttered. But I heard a strangled giggling as she ducked around me with the instruction manual. “Good evening, folks,” she said. Joanna knew I became an involuntary bulimic every time I heard the word “folks.” She squeezed my shoulder hard enough to do structural damage. “Please forgive our trainee.”

She had to admit it, though: They were too terrified to nitpick, passive-aggressively assert their monkey dominance, or whine about anything.

And at the end of the shift, our little tip cup had enough quarters in it for both of us to do our laundry and three dollar bills apiece: A Joe’s Dogs record, and a massive bonus for somebody who, prior to getting punched in the face, was making minimum wage.

Nobody had put the concept of “failing up" into so many words yet. But as you can see, I invented it.

I had planned on staying sober, -ish, that night, in order to finally get a morning to recuperate from the whole suite of events; I was probably still dehydrated from trying to garden with a kitchen knife, and I was only halfway through the job.

But the minute I got home, Leslie grabbed me by the shoulders, put a bottle marked Zima in my paw, and aimed me back at the front door.

“What the fock is this?” I turned the infamous late-20th-century tipple—a bottle of suspiciously clear chemicals, dusted with a sprinkle of synthetic alcohol—over in my hand. “Zima! Did I get lost and walk into a sorority?”

“I have two dozen of them. Do not question the Gods in their bounty.”

“Gods? Of what?” I asked, but I was already in a better mood, giggling as he continued pushing me towards the door; I was already chugging. Zima tasted like brake fluid, but it did the job eventually.

“Wait, where are we going?”

“O’Cayz Corral!”

“What? So why are we leaving now? Nobody’s going onstage till ten.”

“This is a special night. I know these guys. And we need to get to know’em better. I told them about the Incognito Mosquitoes!”

Yes, that was a real band name. Ours. And I named it. Yes, I was dropped on my head. I winced, but not because I had realized it was terrible yet. “OK, but if we get there at nine PM we’re all gonna be trashed before they’re done.”

I had already sucked down the Zima and he had produced another one. I waved it. “See? And I feel like death and smell like a hot dog, just… lemme have ten minutes to take a shower, OK?”

Everyone else at O’Cay’z probably smelled like greasy beer farts, but I had an unterior motive. There was somebody I liked, and this was the night of the week when they were about 75 percent likely to show up at the venue. This is how your social life used to work: Watering holes and percentages. Well, mine, anyway.

“You think that’s going to matter to how trashed I get?” Leslie ran his fingertips, swollen from nail-biting, through his pompadour. This sometimes meant he was scared, sometimes excited, sometimes proud of himself, depending on whether it was followed by more nail chewing. “It only changes the timeframe for me sucking down my dozen.”

“Whatever, Leslie. You know, when a lush like me is worried about how drunk you’re going to get, maybe you’re a pain in the ass.”

“So?”

“Five minutes.” I began to push past him, but then he grabbed me by the shoulder again, scratching his chin.

“Plan to clean yourself up, huh? HUM… Well, we’ll wait for you”—he said “we” because Brett had been standing there in his hair, making the odd faint slurp on his own Zima—“but ya gotta clean up my way.”

I was genuinely confused. “There’s a you way to be clean?? Are you going to puke on me?”

“No, dumbass—Paul’s gone, and that girl Tony used to chuck at the wall?—she left some real rock ‘n’ roll dresses in that closet.”

“Along with several pints of vital fluid, I imagine. You mean slut dresses? He dressed that girl like he was about to stick her on the corner of—”

“Yup!” He rubbed his hands together. “Oh, don’t look at me like that, you know you’re too old and lame for me.”

“Such a shame. So why am I going to a mosh pit naked?”

“It’s more a rockabilly night.”

“Every night is a mosh pit, or are you too drunk to notice?”

“Can’t you trust your bandleader, like, ONCE? This is money on a platter. Hop along and get that wizened 21-year-old ass in the shower.”

Like usual, it was too much trouble to argue with Leslie. So an hour later, I turned up to a punk-rock dumpster full of dead-enders, dressed like a hooker trying to get into the Viper Room. Everyone who knew me did a double take: the black eye was one thing, but did I think I was Molly Ringwald? And half the room knew me. I was only six months past 21, but I had been drinking there since I was 18; it seems strange now, since you need your passport, health records, and a utility bill to get into the grocery store, but at the time that kind of bar never checked ID. They would have gone out of business.

There was one small mercy: my crush wasn’t there, for which I thanked my lucky stars. Me, trying to be sexy, was ridiculous. Shower, yes. Nice clothes, sure. The bottom of my ass cheeks, hanging from synthetic lace? I don’t need to look like I’m drunk already. Anyway, showing a potential mate the red of my fundament like a baboon was hitting a bit too close to home at the moment. Who ELSE thought I was nothing but a neurotic monkey? And what the h£ll kind of caper was Leslie brewing?

Do you really wanna know, Lucille?

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS

Chapter One: At Home in Hotel Hell

Next up… Netty-working!

Brett and Leslie: Chapter Five

Probably half the bar thought I was a neurotic monkey, when I think back. You couldn’t swing a dead cat in O’Cayz without hitting someone who mutually thought I was annoying. Tonight, for example, you had Nick Ridiculous over there in the corner, wearing what looked like children’s pyjama shorts under his bloated gut and that stupid baseball hat covered…